Imagine if everything you thought you knew was upended—like a slow knife-stab to the gut—in a mere two days.

Except I know jackshit. The things I thought I knew came from a lifetime of reading and living in my head: like the precocious Reddit bro I’ve been smugly proselytizing on chemtrails in an isolation tank. Eh do you know the difference between contrails and… cloud seeding?

I attended the first session in my creative non-fiction course last Wednesday. Part of a 6-week program at RMIT University that’s offered to “public, private and community sector professionals and creatives committed to higher communication standards in non fiction writing”, it was the first-ever formal lesson I’d attended since I left high school nearly 15 years ago. The demeanour of the class seemed nervous but rapt, as mature-aged students are when released back into a learning environment. The lecturer was warm—she’d written a memoir and it was laid out on the table in front of us to refer to.

The class was a mixed bag. There was an anthropologist who wanted to learn how to deacademise his writing so that he could eventually publish a Stephen Hawking-esque book. There was a young tabletop RPG player who wanted to write better Dungeons and Dragons plots, and a travel blogger whose favourite creative non-fiction book was Eat Pray Love. There was a design lecturer who professed his love for photo books and someone else who wanted to learn how to not procrastinate writing. Everyone was white and had somehow dropped nearly a thousand bucks of their own money to do the course. Fortunately, I was the last person on the roll.

“I’m a… semi-serious writer who hasn’t gone through any formal training and want to fill in some knowledge gaps,” I said vaguely.

“Beautiful. Lovely.” Those were words the lecturer kept repeating throughout the lesson. When asked, I mentioned that The Women by Hilton Als was my favourite creative non-fic book, even though that wasn’t true. It’s a book I like, but it’s not my absolute favourite. Who the fuck has a favourite? I’ve never even had a best friend.

“Fascinating,” the lecturer beamed upon hearing about my fav in detail. She’d never heard of the book or the author, even though Als is a staff writer at the New Yorker and is in no way obscure. Other people mentioned books like Just Kids by Patti Smith (“also I just really love her music”), Hiroshima by John Hersey and This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff.

It wasn’t all dire. Once I blocked out race and class the lesson started feeling a bit more manageable. The lecturer quoted David Shields—“we live in an age of reality hunger”—and stated that creative non-fiction comes from a place of individual expression, inquiry and doubt. She outlined the differences between “the situation” and “the story”, two factors that would be essential in teasing out the specifics versus the universal. Basically, no one is going to care about your story if you don’t relate it back to them somehow. I cynically wondered if her favourite writer was Vivian Gornick.

Nevertheless, I thought about the question of doubt in writing. Like what lyric essayist Durga Chew-Bose observed in an interview once, “not all writing has to argue a point.” The course lecturer said something similar—you don’t have to have the answers to all the questions you raise. It’s a process of inquiry rather than an act of didacticism; during an attempt at pinning something down, you discover new things that take you in another direction. Maybe you clear something up. Or you expose new challenges. Either way, there’s no easy conclusion and it’s all open to interpretation.

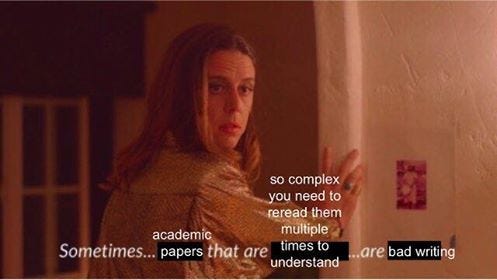

When I met up with Marisa two days later, she listened intently and echoed some of the above. We had a laugh about Eat Pray Love and I awkwardly watched her go over some pieces I’d previously published with a gold glitter pen. Apparently I had subconsciously absorbed certain writing rules relating to structure, so my pieces flowed well. But because I didn’t know the difference between active and passive voice, some of my writing was extremely convoluted. I’m still trying to discern the two.

Being a sucker for punishment, I enjoyed these revelations. Without missing a beat, Marisa narrowed her eyes at me, asking where those inclinations had come from. I responded that it probably stemmed from never having received praise as a child, so I’ve come to normalise criticism as approval. Hurrah, we had slipped into therapist mode again.

But there were other more useful things. One suggestion that may seem really obvious to others but which had never occurred to me before was to read my own writing aloud. A familiar sense of solipsism washed over me. Of course! It’s how you know what it might sound like to someone else.

There’s always an inherent egotism that surrounds writing. After all, to dare to publish your work publicly is to believe your voice matters, and that you have more to offer. It’s why writers like Martin Amis would say that children’s books are beneath him. But relearning what you think you know can be extremely humbling. Sometimes rules can be broken, but you have to learn the rules first. Suddenly, I’m a baby reborn again.

***

This week’s recommendations:

Lur Alghurabi’s brilliant memoir piece New Muslims, New Mosques—“If morality is this black and white aren’t we mostly in the middle, all of us as average and unmemorable as we are?”

Eloise Grills’ stunning visual essay Corio

This conversation between Sheila Heti and Tao Lin in Granta— “I always feel like each sentence has its perfect form, and each paragraph has its perfect form, and so does each chapter, and so does the whole book, and the only way I can see to it is with these constant tweaks.”

Molly O’Neill’s Food Porn, written in 2003 but which still feels very relevant today—“In the early 20th century, when food processing began on an industrial scale, advertisers quickly realized that recipes using their products were potent selling tools. Food manufacturers established test kitchens that created thousands of recipes—using everything from gelatin to canned soup—and distributed the concoctions to food editors. To publications lacking the resources to create their own recipes, these handouts were a boon.”

Brian Dillon’s book Essayism (excerpt here)

Artie Vierkant’s searing essay The Art World’s Health Care Crisis— “Mental illness and drug addiction have come to function as a sort of value-added proposition in artists’ biographies, partly because such issues confirm the myth of the artist existing on the periphery of society.”